100 Trillion Rows Baby

In recently released PyTables 3.8.0 we gave support for an optimized path for writing and reading Table instances with Blosc2 cooperating with the HDF5 machinery. On the blog describing its implementation we have shown how it collaborates with the HDF5 library so as to get top-class I/O performance.

Since then, we have been aware (thanks to Mark Kittisopikul) of the introduction of the H5Dchunk_iter function in HDF5 1.14 series. This predates the functionality of H5Dget_chunk_info, and makes retrieving the offsets of the chunks in the HDF5 file way more efficiently, specially on files with a large number of chunks - H5Dchunk_iter cost is O(n), whereas H5Dget_chunk_info is O(n^2).

As we decided to implement support for H5Dchunk_iter in PyTables, we were curious on the sort of boost this could provide reading tables created from real data. Keep reading for the experiments we've conducted about this.

Effect on (relatively small) datasets

We start by reading a table with real data coming from our usual ERA5 database. We fetched one year (2000 to be specific) of data with five different ERA5 datasets with the same shape and the same coordinates (latitude, longitude and time). This data has been stored on a table with 8 columns with 32 bytes per row and with 9 millions rows (for a grand total of 270 GB); the number of chunks is about 8K.

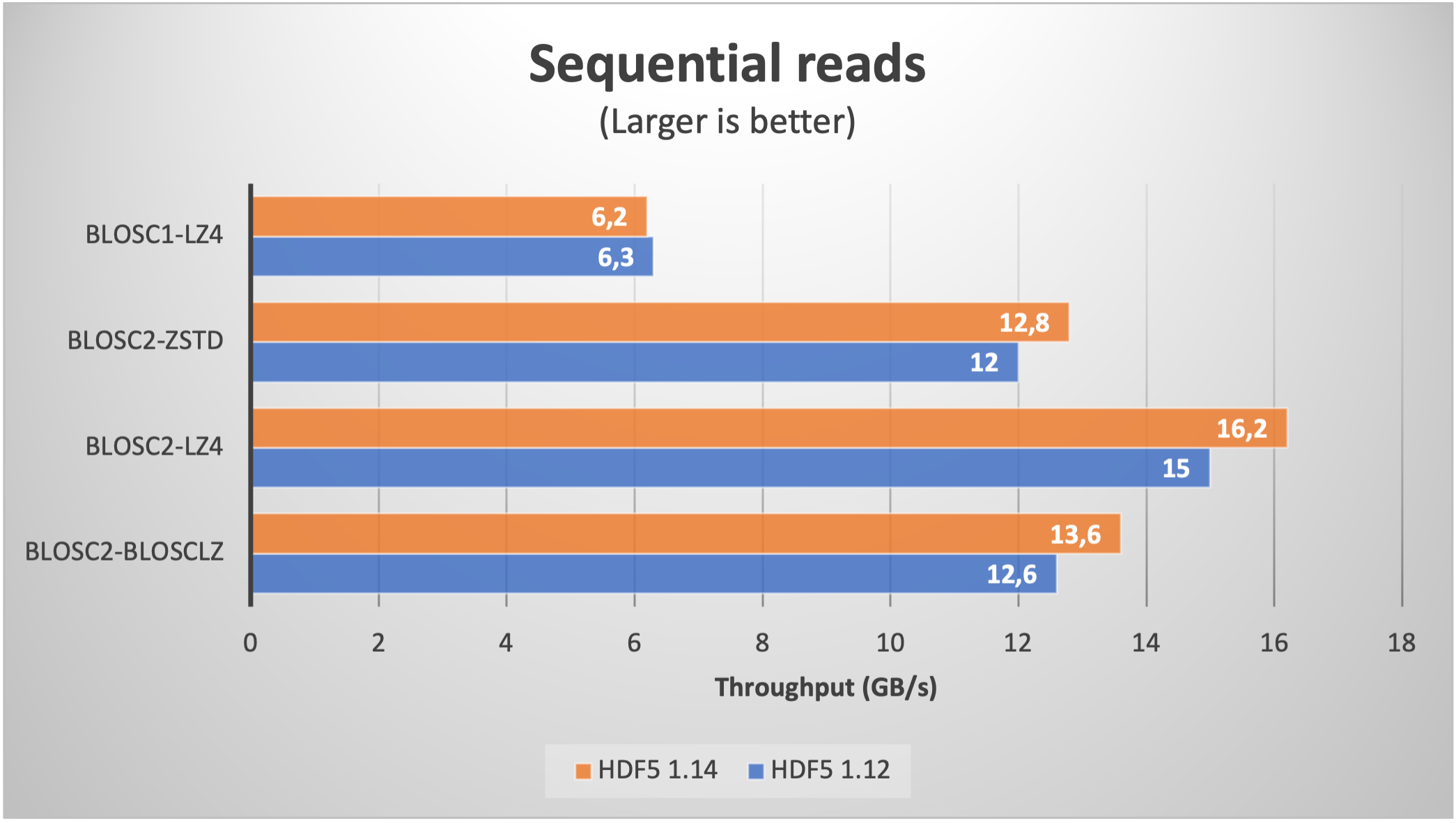

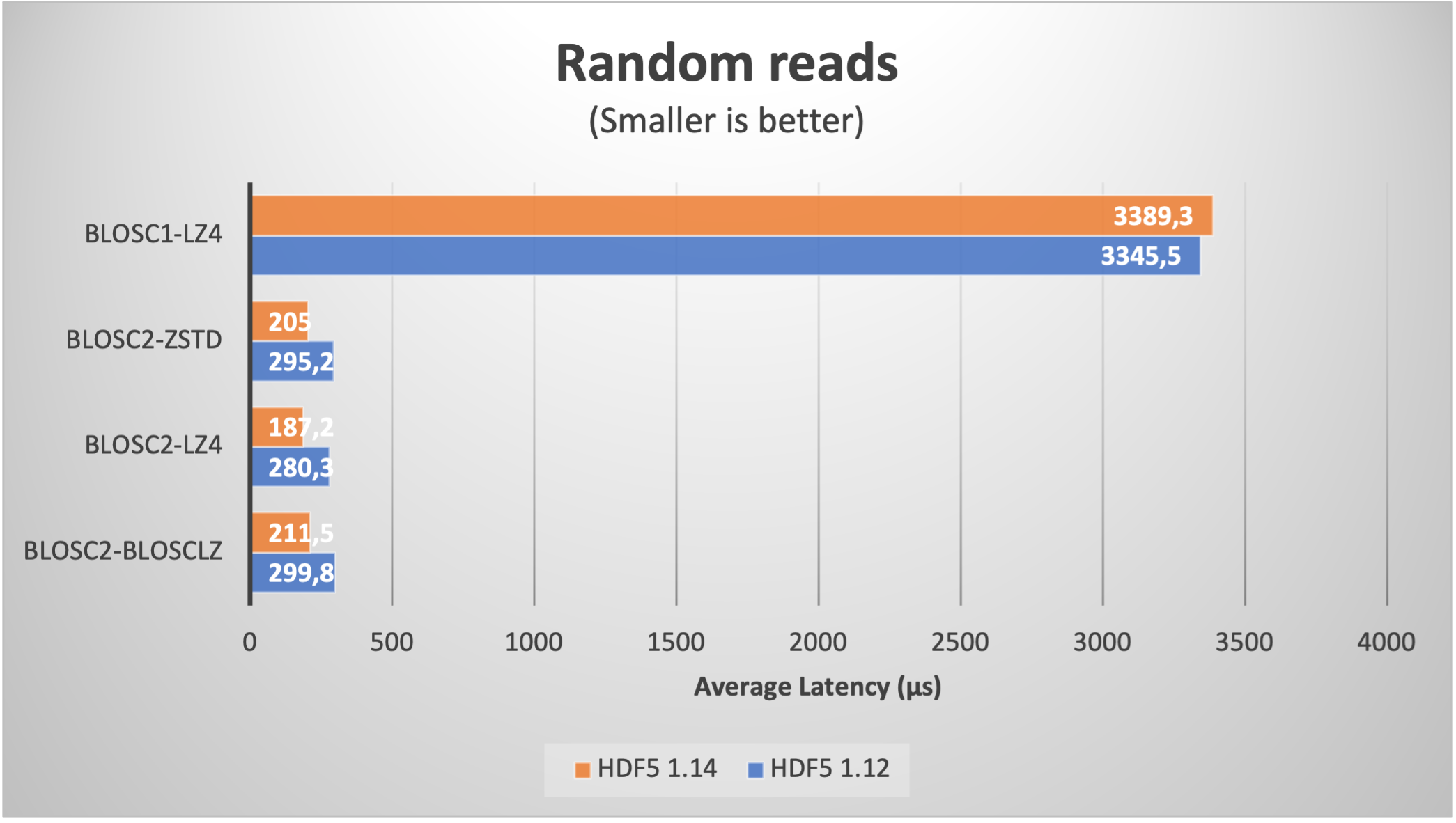

When using compression, the size is typically reduced between a factor of 6x (LZ4 + shuffle) and 9x (Zstd + bitshuffle); in any case, the resulting file size is larger than the RAM available in our box (32 GB), so we can safely exclude OS filesystem caching effects here. Let's have a look at the results on reading this dataset inside PyTables (using shuffle only; for bitshuffle results are just a bit slower):

We see how the improvement when using HDF5 1.14 (and hence H5Dchunk_iter) for reading data sequentially (via a PyTables query) is not that noticeable, but for random queries, the speedup is way more apparent. For comparison purposes, we added the figures for Blosc1+LZ4; one can notice the great job of Blosc2, specially in terms of random reads due to the double partitioning and HDF5 pipeline replacement.

A trillion rows table

But 8K chunks is not such a large figure, and we are interested in using datasets with a larger amount. As it is very time consuming to download large amounts of real data for our benchmarks purposes, we have decided to use synthetic data (basically, a bunch of zeros) just to explore how the new H5Dchunk_iter function scales when handling extremely large datasets in HDF5.

Now we will be creating a large table with 1 trillion rows, with the same 8 fields than in the previous section, but whose values are zeros (remember, we are trying to push HDF5 / Blosc2 to their limits, so data content is not important here). With that, we are getting a table with 845K chunks, which is about 100x more than in the previous section.

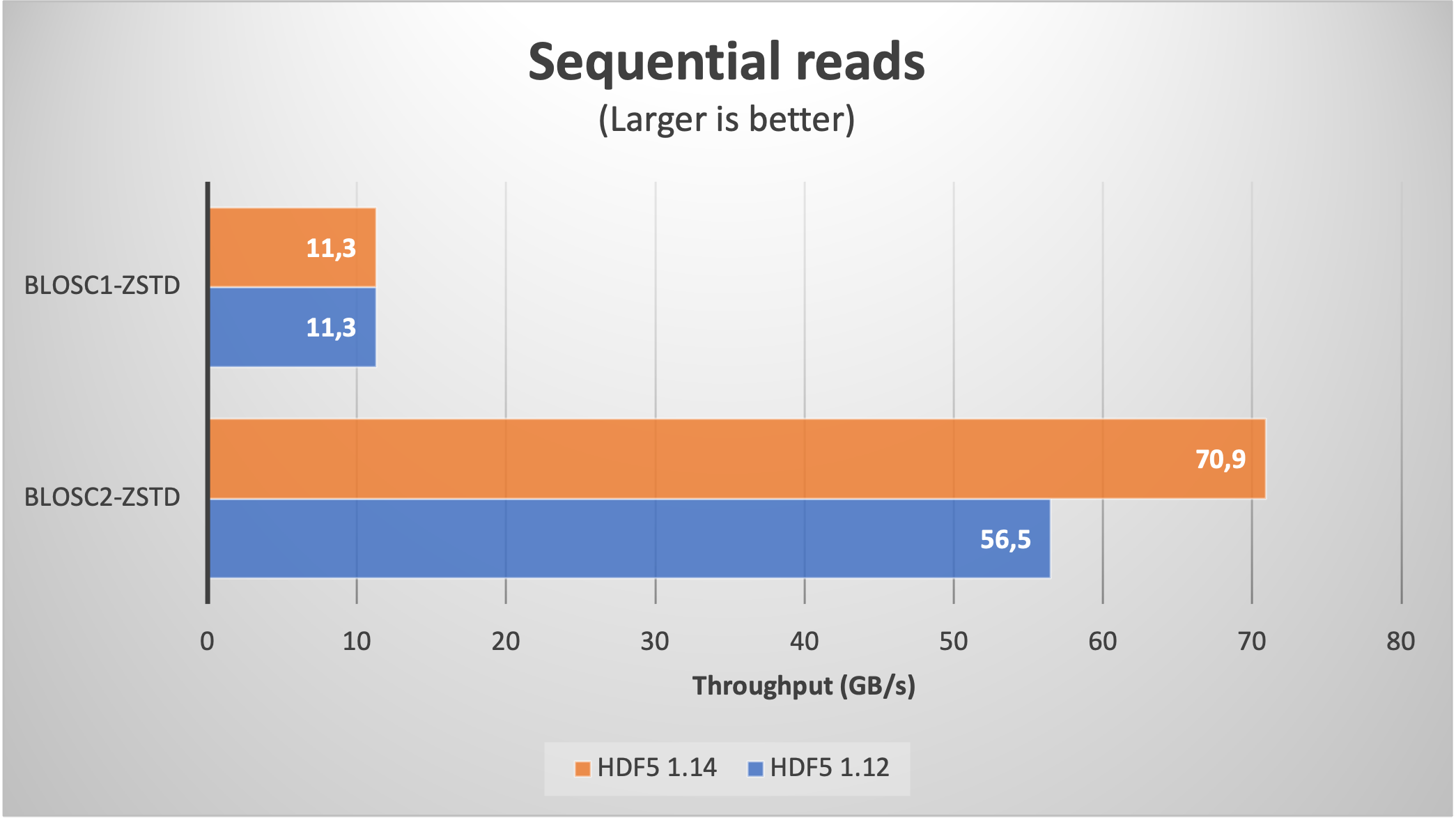

With this, lets' have a look at the plots for the read speed:

As expected, we are getting significantly better results when using HDF5 1.14 (with H5Dchunk_iter) in both sequential and random cases. For comparison purposes, we have added Blosc1-Zstd which does not make use of the new functionality. In particular, note how Blosc1 gets better results for random reads than Blosc2 with HDF5 1.12; as this is somehow unexpected, if you have an explanation, please chime in.

It is worth noting that even though the data are made of zeros, Blosc2 still needs to compress/decompress the full 32 TB thing. And the same goes for numexpr, which is used internally to perform the computations for the query in the sequential read case. This is testimonial of the optimization efforts in the data flow (i.e. avoiding as much memory copies as possible) inside PyTables.

100 trillion rows baby

As a final exercise, we took the previous experiment to the limit, and made a table with 100 trillion (that’s a 1 followed with 14 zeros!) rows and measured different interesting aspects. It is worth noting that the total size for this case is 2.8 PB (petabyte), and the number of chunks is around 85 millions (finally, large enough to fully demonstrate the scalability of the new H5Dchunk_iter functionality).

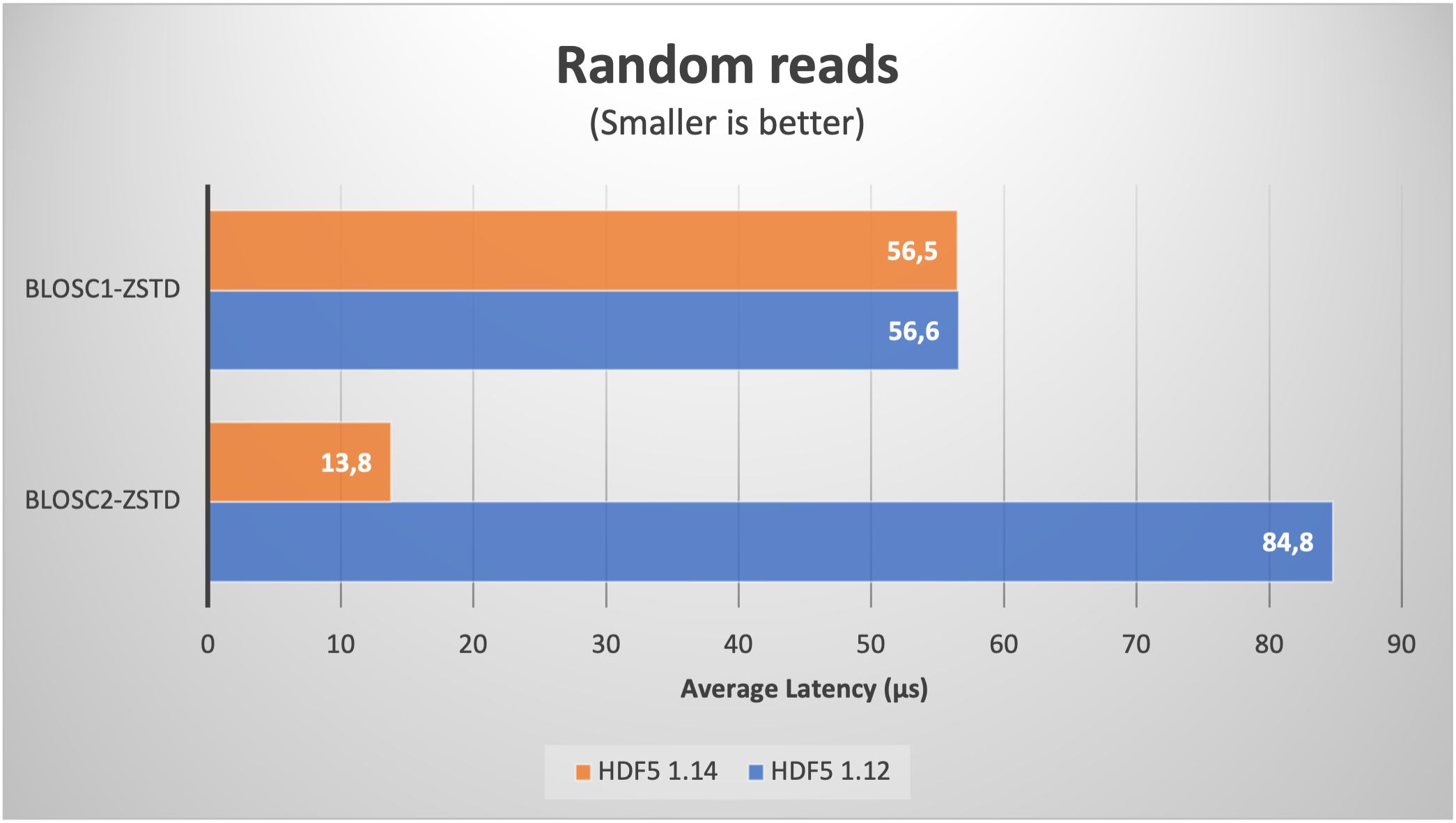

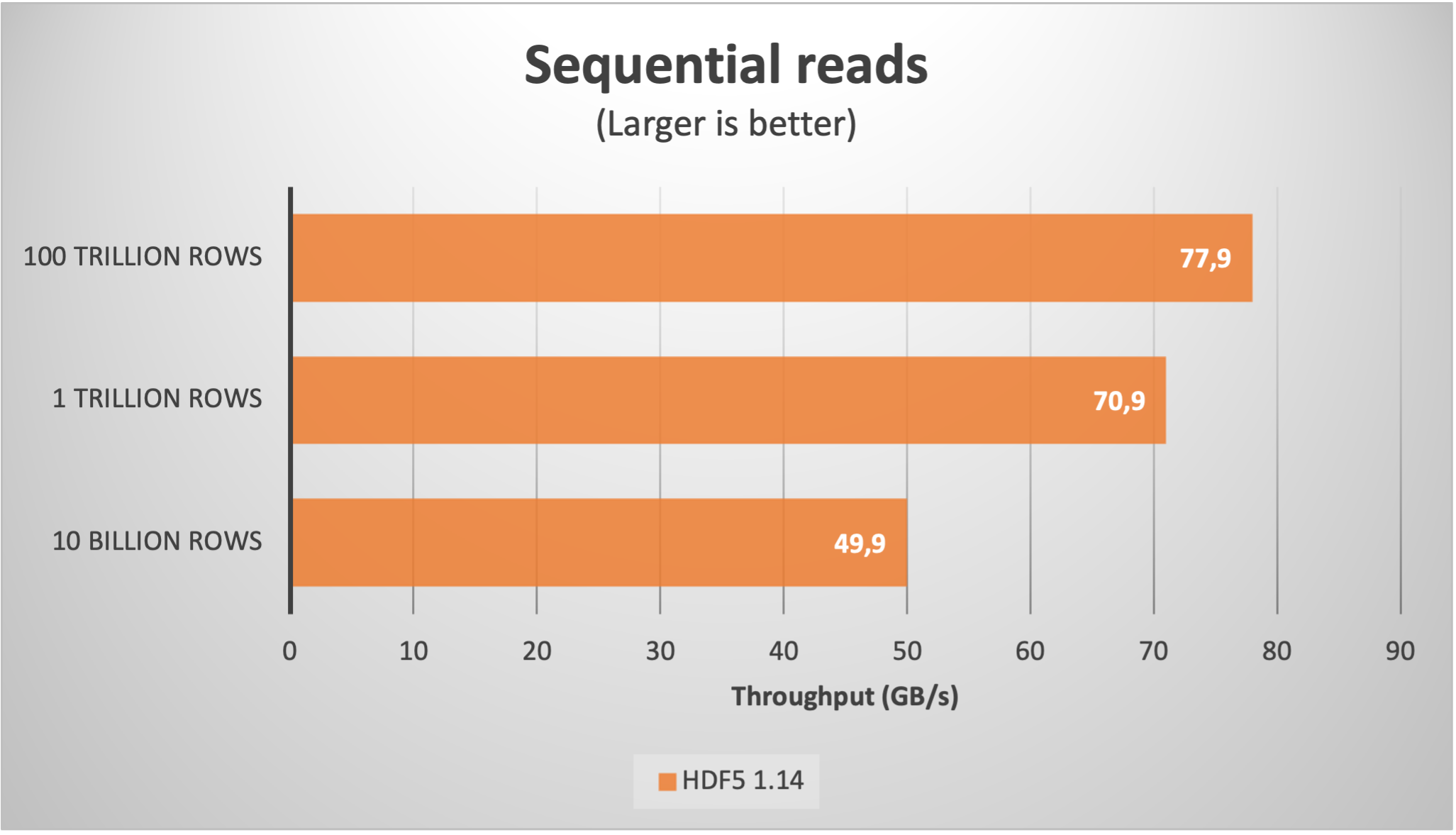

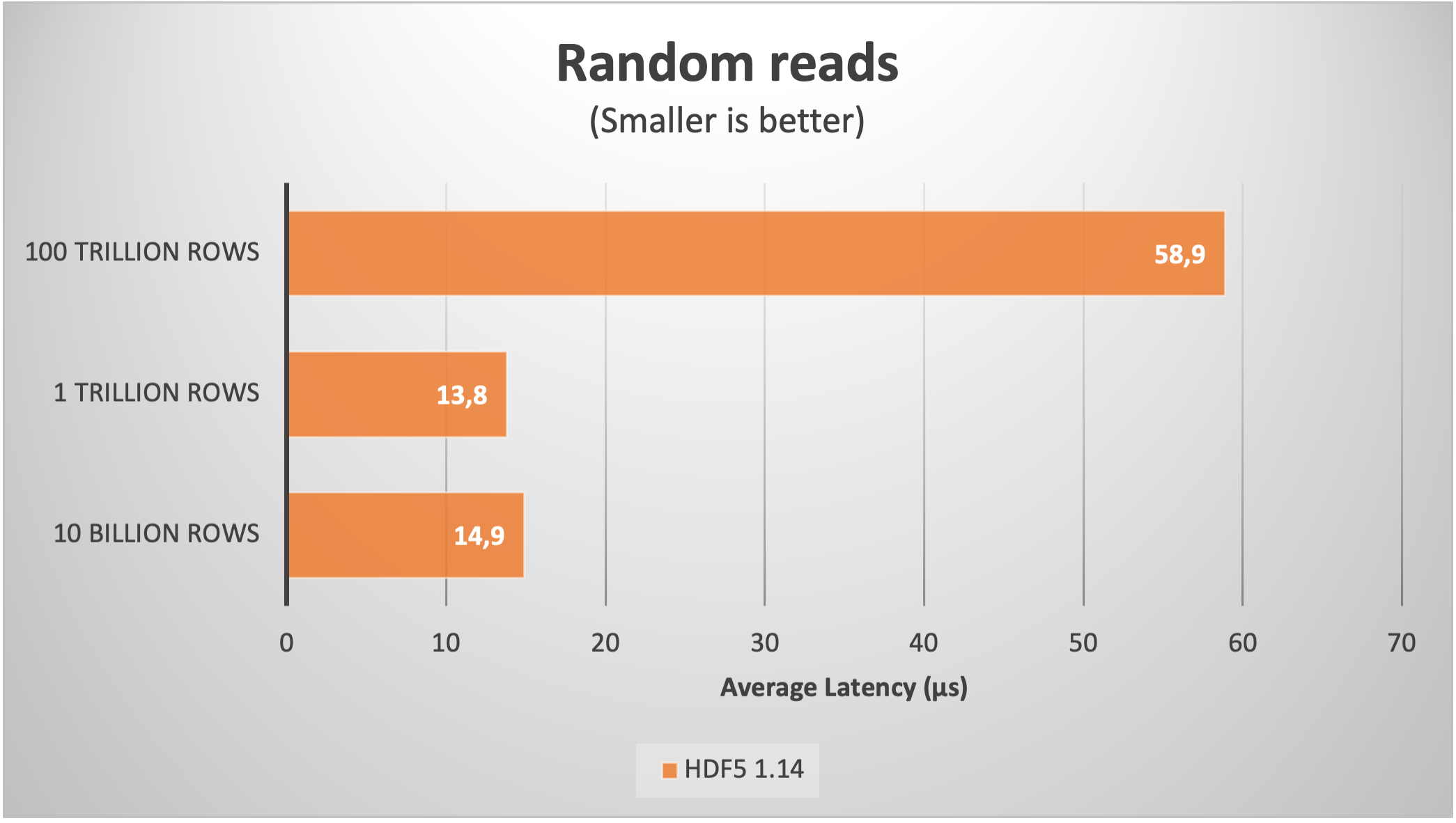

Here it is the speed of random and sequential reads:

As we can see, despite the large amount of chunks, the sequential read speed actually improved up to more than 75 GB/s. Regarding the random read latency, it increased to 60 µs; this is not too bad actually, as in real life the latencies during random reads in such a large files are determined by the storage media, which is no less than 100 µs for the fastest SSDs nowadays.

The script that creates the table and reads it can be found at bench/100-trillion-rows-baby.py. For the curious, it took about 24 hours to run on a Linux box wearing an Intel 13900K CPU with 32 GB of RAM. The memory consumption during writing was about 110 MB, whereas for reading was 1.7 GB steadily (pretty good for a multi-petabyte table). The final size for the file has been 17 GB, for a compression ratio of more than 175000x.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the H5Dchunk_iter function recently introduced in HDF5 1.14 is confirmed to be of a big help in performing reads more efficiently. We have also demonstrated that scalability is excellent, reaching phenomenal sequential speeds (exceeding 75 GB/s with synthetic data) that cannot be easily achieved by the most modern I/O subsystems, and hence avoiding unnecessary bottlenecks.

Indeed, the combo HDF5 / Blosc2 is able to handle monster sized tables (on the petabyte ballpark) without becoming a significant bottleneck in performance. Not that you need to handle such a sheer amount of data anytime soon, but it is always reassuring to use a tool that is not going to take a step back in daunting scenarios like this.

If you regularly store and process large datasets and need advice to partition your data, or choosing the best combination of codec, filters, chunk and block sizes, or many other aspects of compression, do not hesitate to contact the Blosc team at contact (at) blosc.org. We have more than 30 years of cumulated experience in storage systems like HDF5, Blosc and efficient I/O in general; but most importantly, we have the ability to integrate these innovative technologies quickly into your products, enabling a faster access to these innovations.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus