Miniexpr-Powered Blosc2: Beating the Memory Wall (Again)

In my previous post, The Surprising Speed of Compressed Data: A Roofline Story, I showed that Blosc2 could shine in out-of-core workloads, but for in-memory, low-intensity computations it often lagged behind Numexpr. That result was so counter-intuitive that it motivated a new effort: miniexpr, a block-level expression engine designed to evaluate Blosc2 blocks in parallel and keep the working set in L1/L2 as much as possible.

This post shows what changed.

TL;DR

The new miniexpr path dramatically improves low-intensity performance in memory.

The biggest gains are in the very-low/low kernels where cache traffic dominates.

High-intensity (compute-bound) workloads remain essentially unchanged, as expected.

There is one regression: AMD on-disk uncompressed got slower; we call that out below.

Before/After: A Quick Look

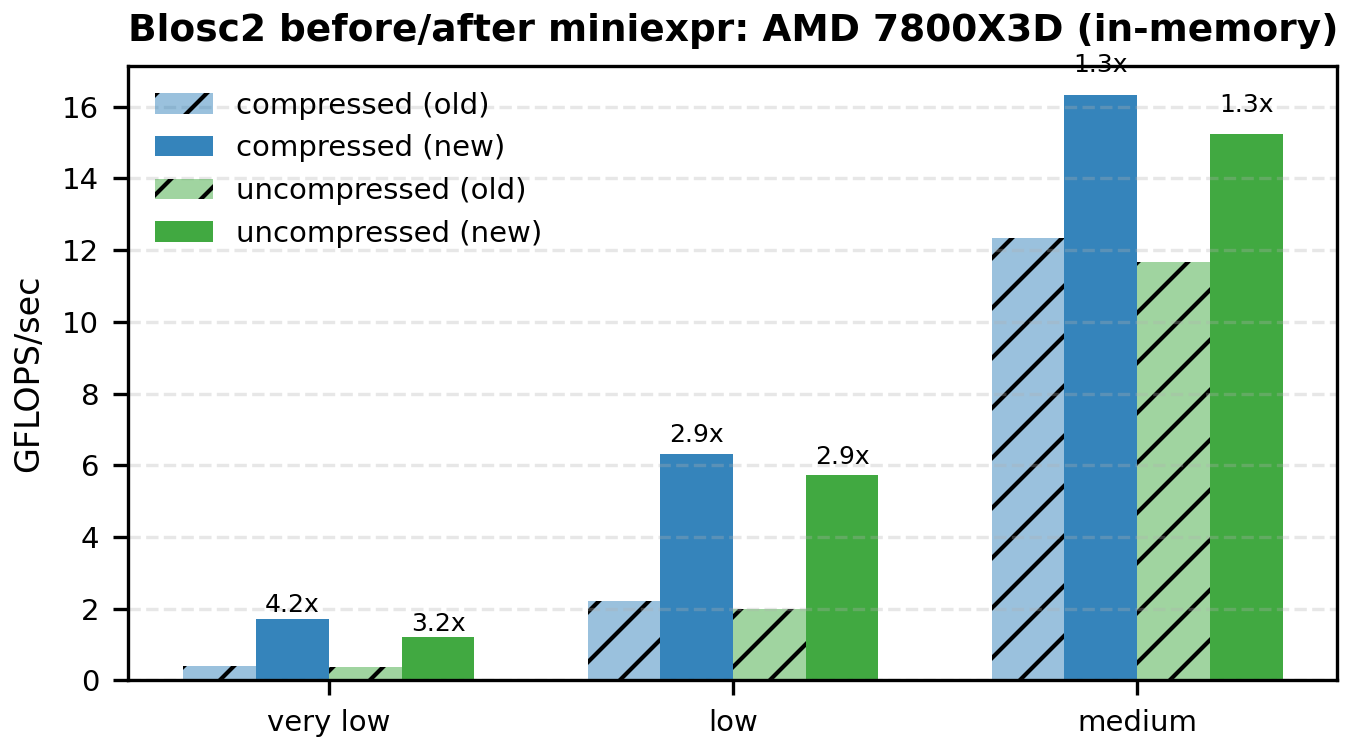

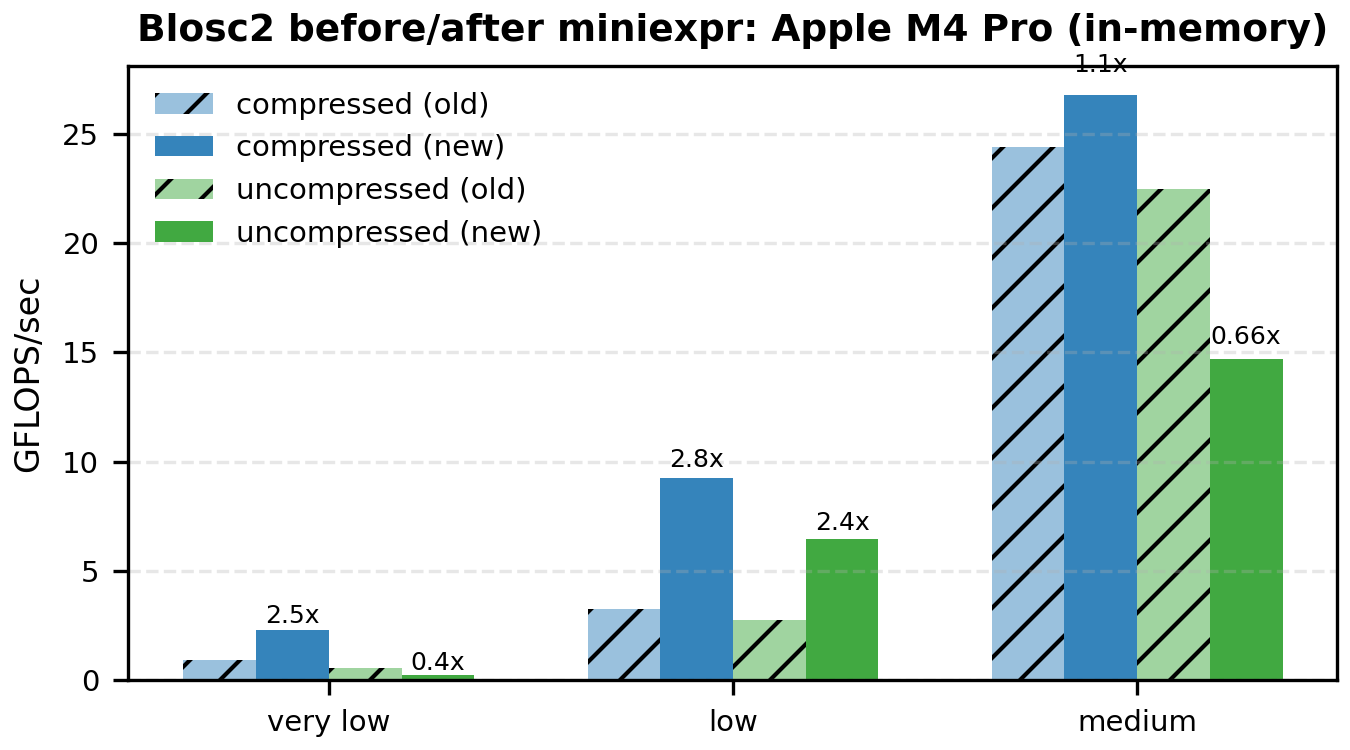

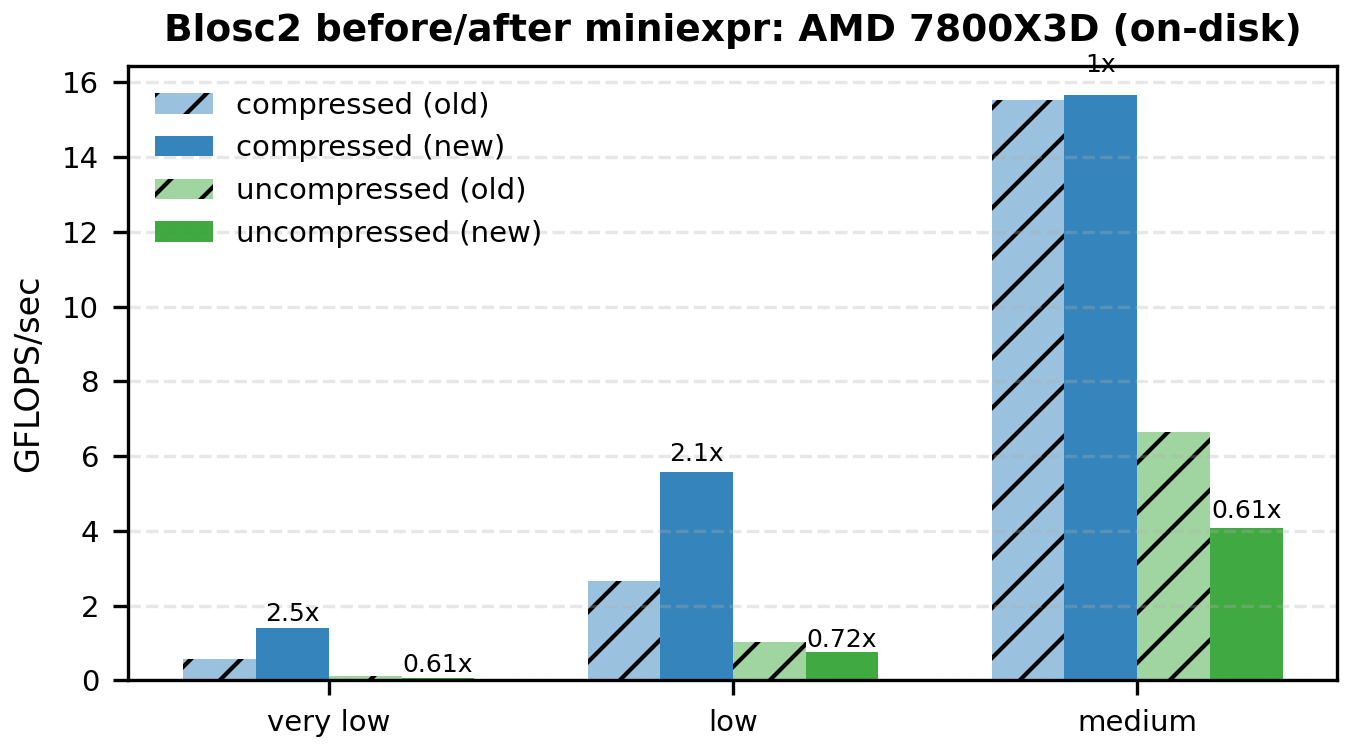

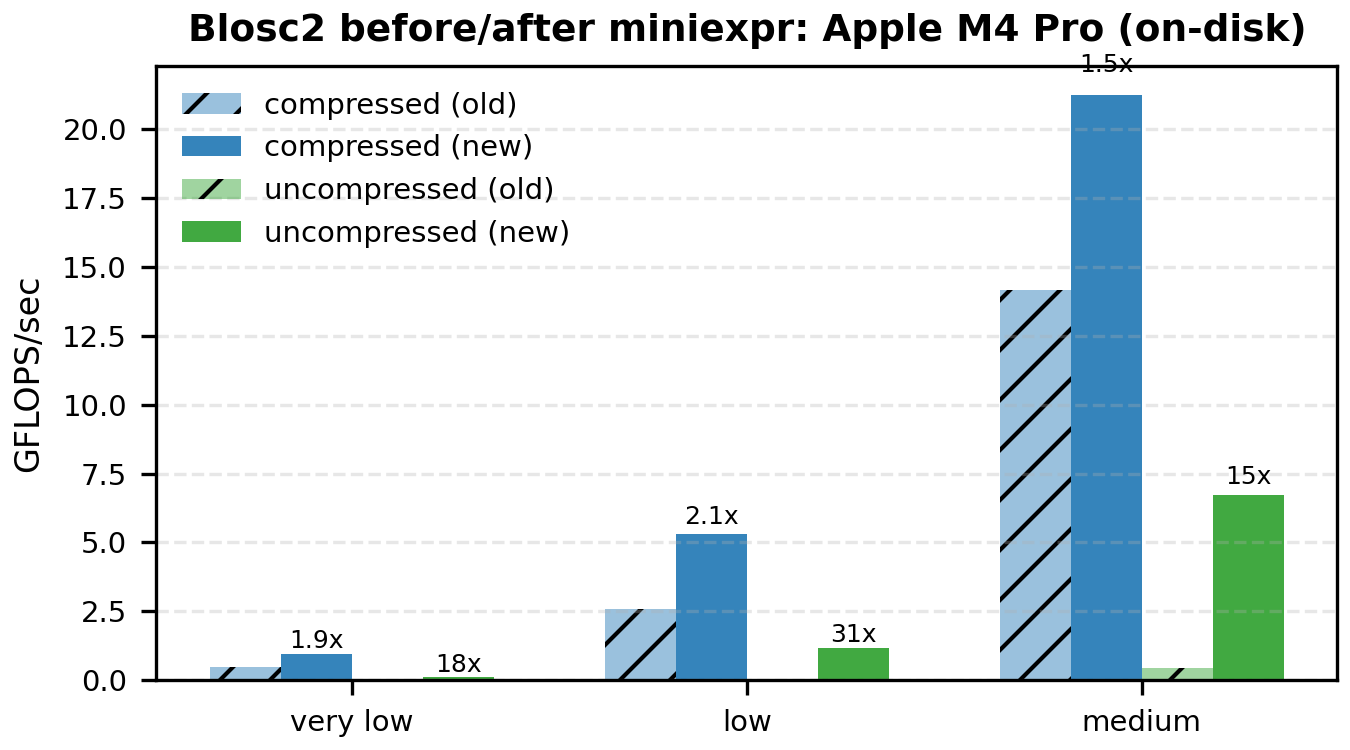

The following bar plots compare old vs miniexpr for Blosc2 (compressed and uncompressed). I'm showing only the low-to-medium intensities, because that's where the memory wall dominates and the changes are most visible.

Mini Tables (Compressed Blosc2, GFLOPS)

Roofline Context

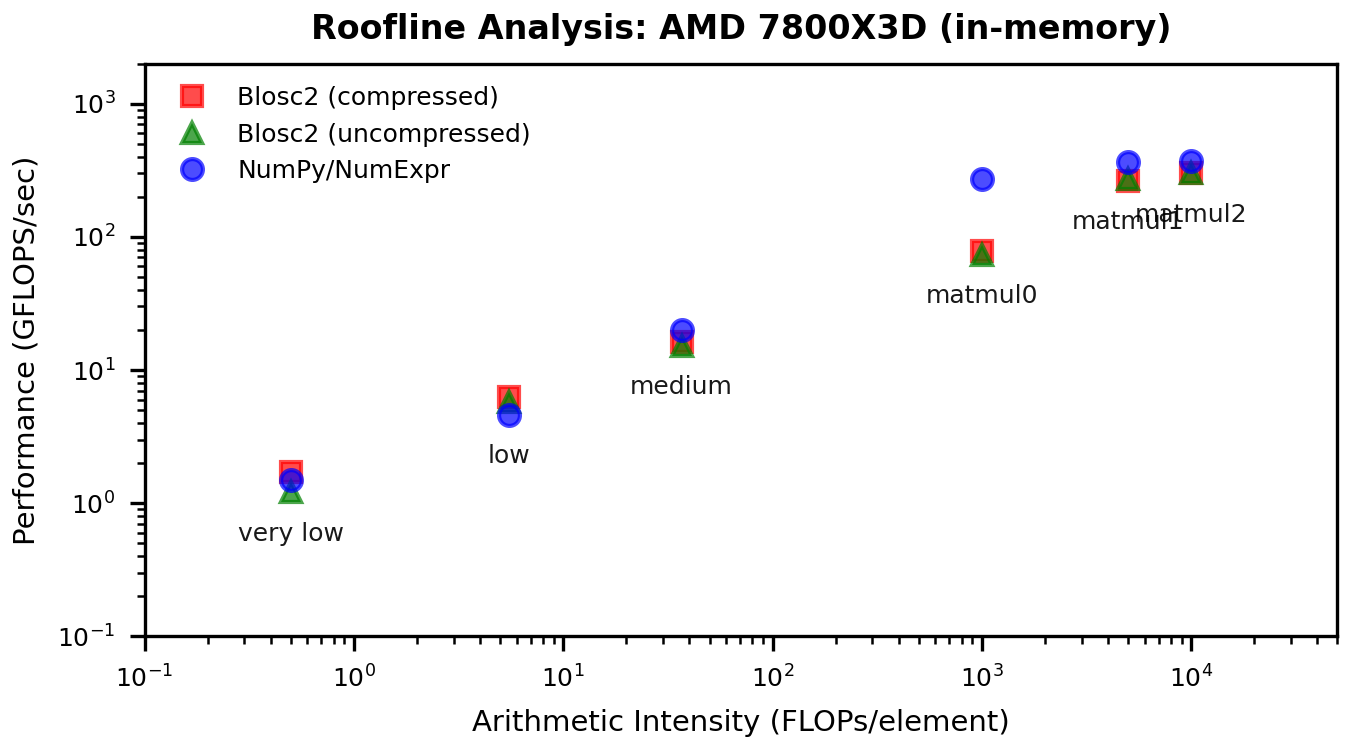

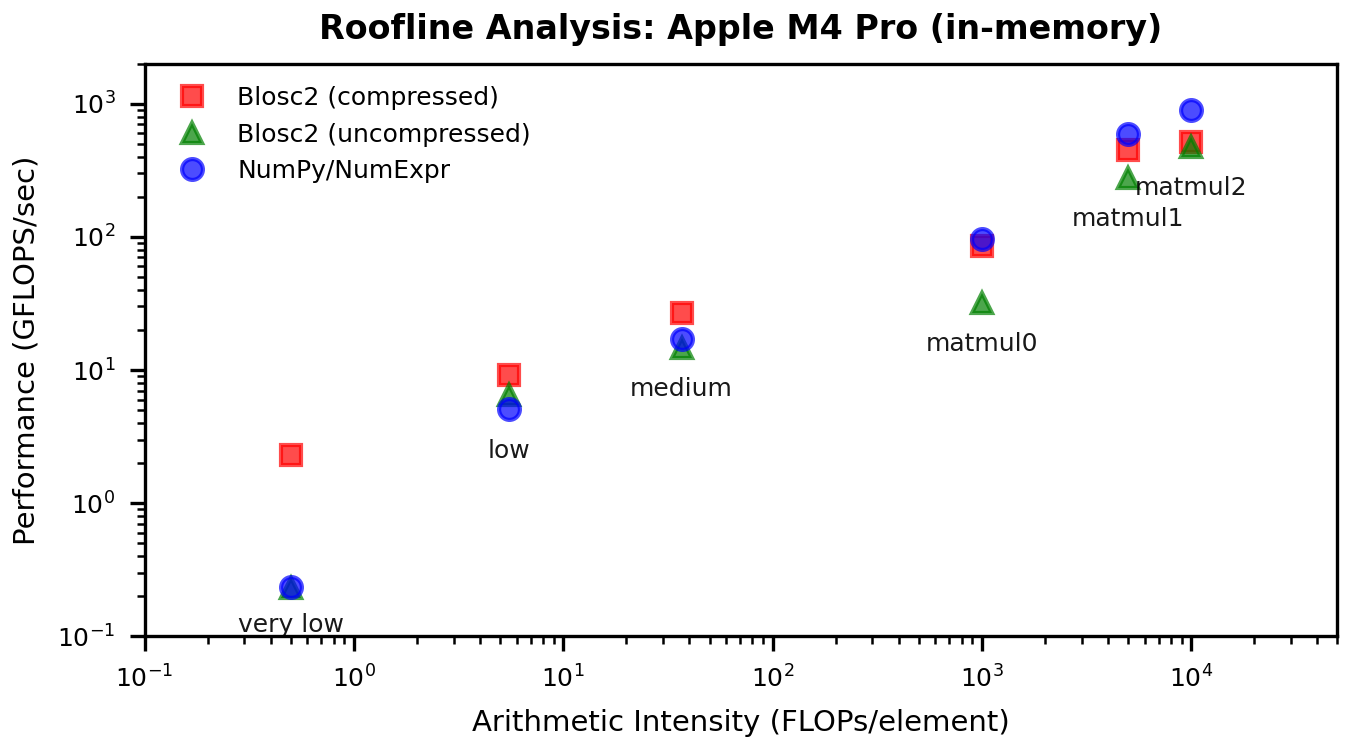

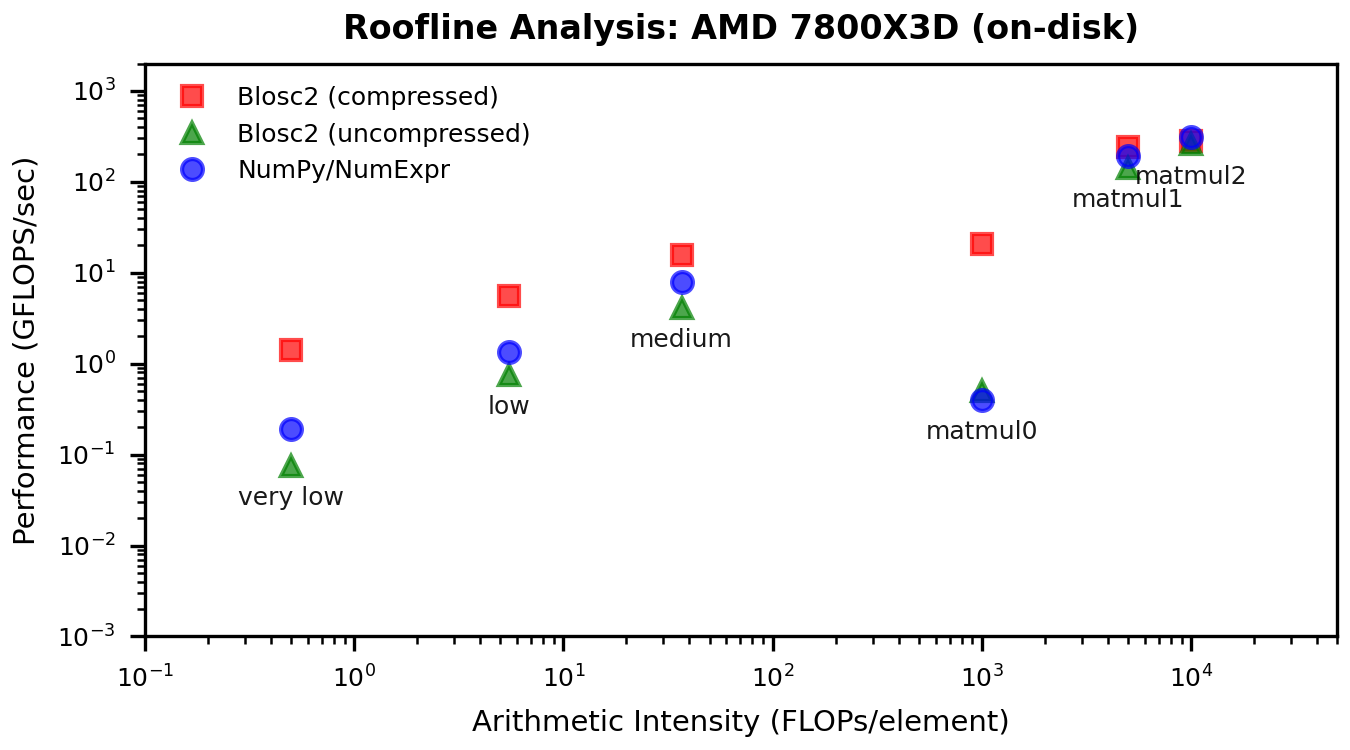

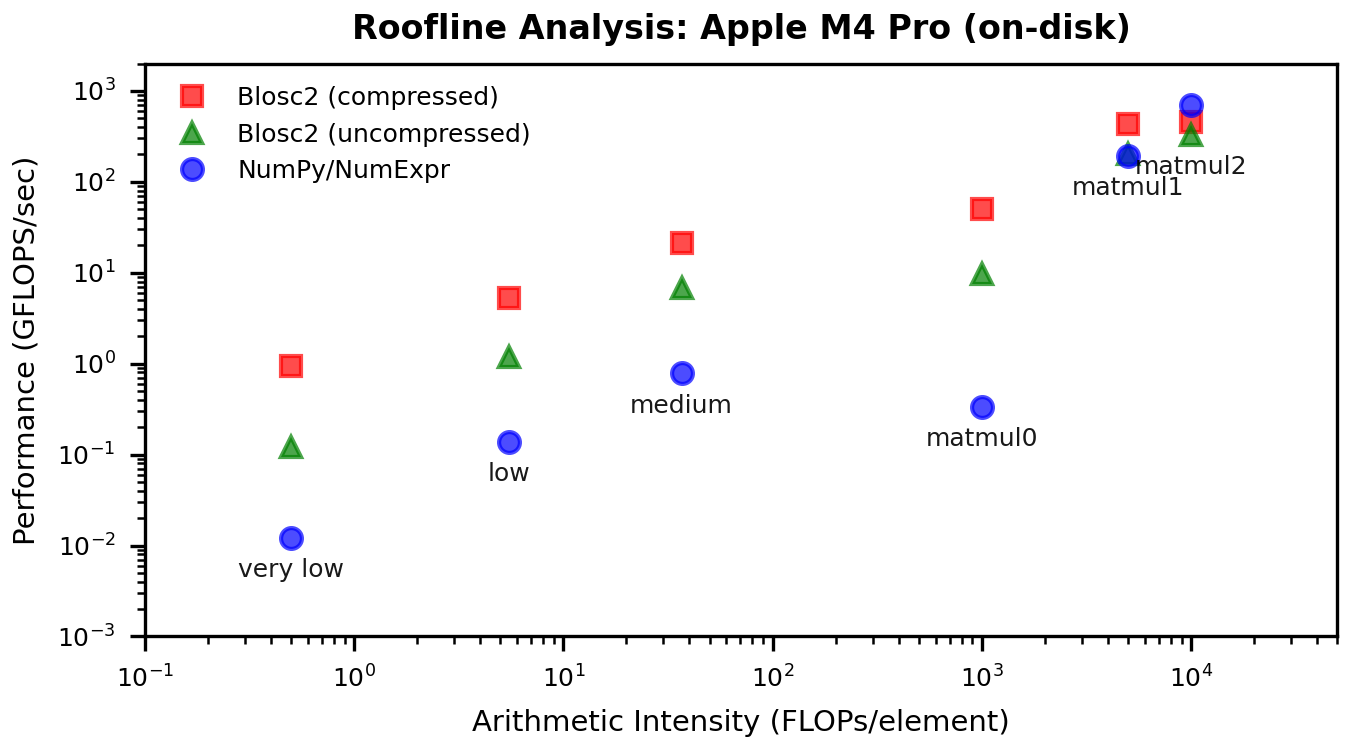

To connect the "before/after" gains to the memory wall, here are the updated roofline plots. These show how the low-intensity points move up without changing arithmetic intensity--exactly what we expect when cache traffic is reduced.

Discussion: What Changed?

In the original post I attributed the low-intensity slowdown mainly to indexing overhead when extracting operand chunks. The new results suggest a different dominant cost: cache traffic. The old path evaluates whole chunks per operand, which inflates the working set beyond L2/L1 and pushes a lot of data through L3 and memory. With miniexpr, computation happens on much finer blocks in parallel, keeping most traffic in L1/L2 and shrinking the working set per thread. The roofline behavior matches this: very-low and low intensities jump up sharply, while high-intensity points are essentially unchanged.

Indexing still matters, but it is minimized when operands share the same chunk and block shapes. This alignment is common for large arrays with a consistent storage layout, and when it holds, miniexpr delivers the big gains shown above. When it doesn't, python-blosc2 automatically falls back to the previous chunk/numexpr path, preserving coverage and correctness while trading off some performance.

A note on baselines: on my current Mac runs, the Numexpr in-memory baseline is lower than in the original post. I re-ran the benchmark several times and the numbers are stable, but I did not pin down the exact cause (BLAS build or dataset/layout differences are plausible). The comparisons here are still apples-to-apples because all runs are from the same environment.

A Note on Regressions

There is one case where results regress: AMD on-disk, uncompressed. The most plausible explanation is I/O overlap. In the previous chunk/numexpr path, the next chunk could be read in parallel while worker threads were computing on the current one. In the miniexpr path, all blocks of a chunk must be read sequentially before the block-level compute phase starts, so that overlap is largely lost. This would disproportionately hurt the on-disk, uncompressed case on AMD/Linux. The curious part is that Apple on-disk, uncompressed improves, which suggests that parallel chunk reads were not helping much on macOS (for reasons we do not yet understand). We will keep investigating.

Conclusions

Miniexpr flips the "surprising story" from the previous post. In-memory, low-intensity kernels--the classic memory-wall case--now see large gains, while compute-bound workloads behave as expected. The roofline shifts confirm the diagnosis: this is a cache-traffic problem, and miniexpr fixes it by working at the block level.

This is a big step forward for "compute-on-compressed-data" in Python, and a strong foundation for future work (including the remaining on-disk regression).

Read more about ironArray SLU -- the company behind Blosc2, Caterva2, Numexpr and other high-performance data processing libraries.

Compress Better, Compute Bigger!

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus